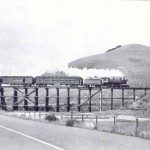

Tiburon’s trestle

Hobos sat on railroad flat cars and waved as we stood on the picnic table in our backyard and waved back. Trains rolled through both tunnels, two miles south to Tiburon. Tiburon Boulevard’s forty-foot trestle was close to the south tunnel, and parents had forbidden us to to cross it. We crossed it anyway, connecting to land near the sewer treatment plant by Blackie’s Pasture. Blackie was an old silent film horse who lived in the pasture below the trestle with a white horse name Whitey. Both horses seemed forgotten.

My friend Tracy and I stayed up all night, mixing and drinking vodka, vermouth, cheap bourbon, scotch, and sherry in jelly jars. I gave her piggyback rides around her bedroom and we laughed, stumbled, felt sick, and knew something wasn’t right, but didn’t know what was wrong.

Tracy said she needed to go a Roman Catholic Mass, so we decided stay up all night and walk across the trestle at dawn. We went through the tunnel onto the trestle and crossed it, looking over our shoulders for an oncoming train, even though no train had been on the track for at least a couple of months. No car stopped for the driver to yell, “Get down from there, don’t you kids know how dangerous that trestle is?” Yeah, we knew.

“What would you do if a train came?” I asked as we inched our way across the endless.

“I’d jump down on one of those,” not taking her eyes off the ties, Tracy indicated her shoulder toward huge horizontal wooden beams supporting the track.

“If we put our ear to the rail, we can hear trains and have time to run.”

“I can barely walk like this. I’m not lying down.” She was not laughing.

“I’ll do it.”

“Yeah, right.” She was freaked.

I stopped and laid down on gooey black ties, resting my head on the shiny rail.

“Jesus. . .” Tracy said, tip-toeing her way.

Leave a Reply